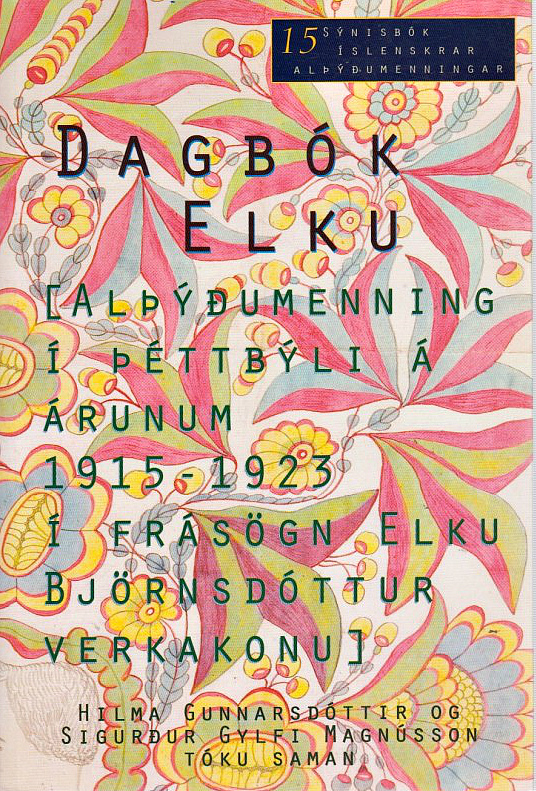

The Diary of Elka. Popular culture in urban areas in 1915–1923 seen with the eyes of the working-class woman, Elka Björnsdóttir. Anthology from Icelandic Popular Culture 15. Published by the University of Iceland Press, 2012. Co-author: Hilma Gunnarsdóttir. 330 pages. – (Dagbók Elku. Alþýðumenning í þéttbýli á árunum 1915–1923 í frásögn Elku Björnsdóttur verkakonu. Sýnibók íslenskrar alþýðumenningar 15 (Reykjavík: Háskólaútgáfan, 2012)).

The Diary of Elka. Popular culture in urban areas in 1915–1923 seen with the eyes of the working-class woman, Elka Björnsdóttir. Anthology from Icelandic Popular Culture 15. Published by the University of Iceland Press, 2012. Co-author: Hilma Gunnarsdóttir. 330 pages. – (Dagbók Elku. Alþýðumenning í þéttbýli á árunum 1915–1923 í frásögn Elku Björnsdóttur verkakonu. Sýnibók íslenskrar alþýðumenningar 15 (Reykjavík: Háskólaútgáfan, 2012)).

The methods of microhistory are applied to the narrative of one woman’s life – Elka Björnsdóttir. She was a working class woman in Reykjavik, Iceland, at a critical time in the development of the city; when the country was moving slowly but steadily from a peasant social structure towards an urban way of living. The life of Elka Björnsdóttir provides an interesting opportunity to analyse how old ways die hard – how the Icelandic society managed to take aggressive, yet progressive, steps to a more modern society in the early 20th century without ever losing its sight on traditional cultural standards. This process is here named ‘Selective modernization’ and illustration of its effect on the Icelandic peoples’ general outlook on life is provided.

Elka Björnsdóttir was hardly a well-known figure in her own time. But her name crops up sporadically in historical discussion of the turbulent times that characterized Reykjavík in the early part of the 20th century. This interest stems from the diaries that she kept over the years 1915-1923, which contain eye-witness accounts of everyday life in an unsettled and rapidly growing urban society. Elka Björnsdóttir died in February 1924, aged only 43, after a long struggle with poverty and ill-health. She had lived and worked in Reykjavík since 1906 and remained unmarried and childless throughout her life. Elka was a working woman, with a firm religious faith and an interest in labor issues, education, culture and progress, uncowed by those more powerful than herself, and with a strong sense of social justice. Urban culture, though still in an embryonic stage, sat well with Elka, though, as noted later, she often looked askance at its frivolity and the hustle and bustle of the new town. She attended church regularly. Despite her limited means, she took a keen interest in cultural events and was an active participant in politics and the movement for workers’ rights. She was one of the very few female members of Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag (The Icelandic Literary Society) and a keen attendee at its lectures and meetings, was a founder member of Alþýðuflokkurinn (The Social Democratic Party) and sat on the founding council of Verkakvennafélagið Framsókn, the first trade union in Iceland to represent women’s interests. But, still, she would not be labeled as part of the working elite; in fact, she was just a regular working woman.

Elka was born at the farm of Reykir in Lundareykjadalur, western Iceland, on 7 September 1881 and grew up at Skálabrekka in Þingvallasveit from the age of two. She moved to Reykjavík in her mid twenties. For the first few years she worked in domestic service in middle-class households before turning to laboring jobs such as herring salting and salt-fish processing. Later she worked as a washerwoman at the hot-springs that served as a laundry site just outside town, and as a domestic cleaner, including at the offices of the mayor of Reykjavík and, from 1917, at the central fire station. Most of her life she lived in rented accommodation in various parts of town, sometimes with relatives, and never far from destitution.

In her diary Elka describes both her day-to-day activities and events of a wider significance. Sometimes she is a spectator, more often a participant in what she relates. The diary provides rare testimony of the living conditions of the section of the population about whom we generally hear the least, working women in Reykjavík in the early years of the 20th century. Life was a daily struggle for Elka but she always tried to hold her head up in spite of her limited resources, irregular work, and poor housing. Perhaps most poignant of all was people’s helplessness in the face of disease, as witnessed eloquently in Elka’s detailed account of her brother’s death and her own battle with ill-health.