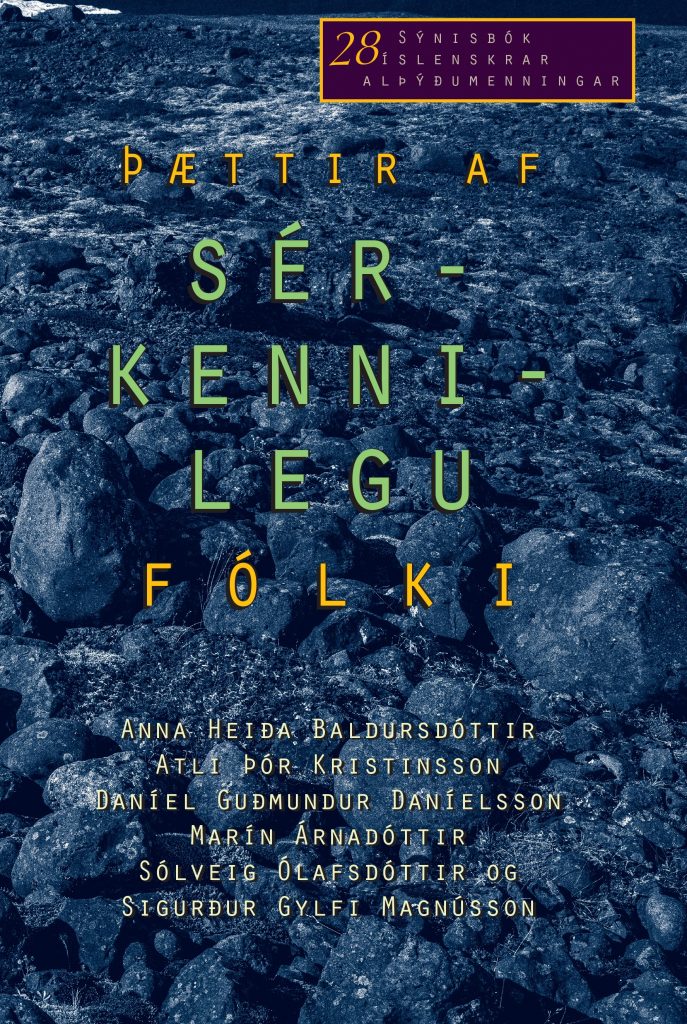

Anna Heiða Baldursdóttir,Atli Þór Kristinsson, Daníel Guðmundur Daníelsson,Marín Árnadóttir, Sólveig Ólafsdóttir andSigurður Gylfi Magnússon, Tales of Peculiar People: The Culture of Poverty. Anthology of Icelandic Popular Culture 28. Reykjavík: University of Iceland Press, 2021.

What is it that makes someone unusual, that distinguishes a person from their peers, most of whom society considers “normal” (a phenomenon that does not actually exist, of course)? That is the question at the center of Tales of Peculiar People. The book attempts to understand what is behind the idea of “normal” and considers deviations from so-called normal behavior or customs. When it comes to defining who belongs to the majority – and at the same time, by default, who is relegated to the minority – the idea of “otherness” is key. But ultimately, it all comes down to power; specifically, the power some groups hold to dictate what constitutes “normal” or “abnormal” behavior and, in so doing, to decide the fate of others. Such power tends to lead to the emergence of certain norms based on a hierarchy that has often been constructed over a long period of time. Understanding “the other” requires delving into how social identities are formed and identifying the most important factors that come into play. From a societal perspective, social identity is natural, something that arises organically from a country’s cultural environment; in other words, it is ingrained from birth. From a social perspective,on the other hand, identityis most often examined in terms of communication patterns and categories like gender, race, class, nationality, etc. – in other words, by how we want others to see us and the groups to which we belong. Identity, therefore, is continually being shaped and undergoes significant changes on a regular basis, even as the foundation remains the same or very similar.

People frequently compare themselves with others; what do two or more individuals have in common, and what distinguishes them from each other? In a certain sense, comparison is a central component of human existence; however, it also leads to the exclusion of certain groups and even the singling out of specific behaviors or points of view that deviate from prevailing norms. As a result, an “us” and “them” dichotomy emerges.

The book Tales of Peculiar People: The Culture of Poverty is about individuals who were considered unusual and existed on the margins of society. Some were socially disadvantaged and had nowhere to call home. Others, having struggled with poverty or other hardships, found themselves teetering on the edge of society at some point in their lives. Subjected to the scrutiny of their peers, they were often cruelly mistreated and ridiculed, making their lives all but unbearable at times.

Sigurður Gylfi Magnússon leads off the book with a discussion of so-called freaks, people who looked or behaved differently in some way. Though they usually lived in difficult circumstances, many were eventually able to earn a living by appearing in “freak shows” around the world. Freak shows were a complicated phenomenon that draw attention to importantaspects of many Western societies. This history is partly recounted in the article “Where are the Freaks Found?”, intended as an introduction of sorts to the rest of the book, which focuses on peculiar people in Iceland.

There is no doubt that Icelanders were greatly interestedin all sorts of fantastical tales.Indeed, accounts of the peculiarcan be found in annals, travel narratives, and other manuscripts from centuries past. In an article titled “Curiosities and Exotic Lands,” Atli Þór Kristinsson traces this great fascination up to the end of the 19th century.

But who exactly made up this band of misfits? Anna Heiða Baldursdóttir writes about workers who lived in abject poverty, demonstrating just how little it took to derail them from their day-to-day struggles and force them to the fringes of society. In fact, a large part of the population straddled the line between average living conditions and utter destitution. Anna Heiða’s article, titled “An Account of the Poorest Workers’ Possessions,” considers the situation that those who had almost nothing to their names faced on a regular basis.

Anna Heiða Baldursdóttir’s article is followed by two others that explore society’s treatment of a few individuals who endured great suffering: Marín Árnadóttir’s “Bullying and Violence in Stories of Peculiar People: Solveig Eiríksdóttir and Jón Gissurarson” and Sólveig Ólafsdóttir’s “Jón Gissurarson and Solveig Eiríksdóttir’s Life Threads: Afterword and Methodology.” Marín Árnadóttir and Sólveig Ólafsdóttir focus their attention on the same two individuals, each in her own way. Marín goes one step further by revealing the culture of bullying that permeated Icelandic society in past centuries.

Finally, the book features four bibliographies. Three were compiled by Daníel Guðmundur Daníelsson, who researched a type of text that was once popular in Icelandic periodicals, appearing in both the Proceedings of the Icelandic Parliament and the Annals, 1400–1800,for instance. These texts, essentially descriptions of people’s mental and physical condition and other characteristics, illuminate contemporary attitudes to those on the outskirts of society. The fourth bibliography, compiled by Marín Árnadóttir, is a list of published books, articles, and periodicals that discuss marginalized people. The book’s authors hope that these bibliographies will aid future scholars conducting research on this important topic.

Diving deeper into documentation of outcasts’ lives often gives researchers the opportunity to see the topic from a new perspective, as many of the researchers whose work is presented here have done. The book gives accounts of people who were somehow swept off the path of ordinary life and frequently forced to contend with the day-to-day struggles of existence from the periphery. Telling their stories presents an opportunity to draw attention to the more serious side of their situations and daily lives, which seem to have been frequently characterized by casual or slow violence and bullying. The book considers whether this mistreatment amounted to a culture of violence and bullying that essentially empowered the majority to target people who were different and make jokes at their expense. The authors also discuss what precautions should be taken when examining sources that are part of the local tale tradition, and, moreover, explain the opportunity they represent to shed new light on certain aspects of Icelandic popular culture and on fringe members of society in previous centuries.