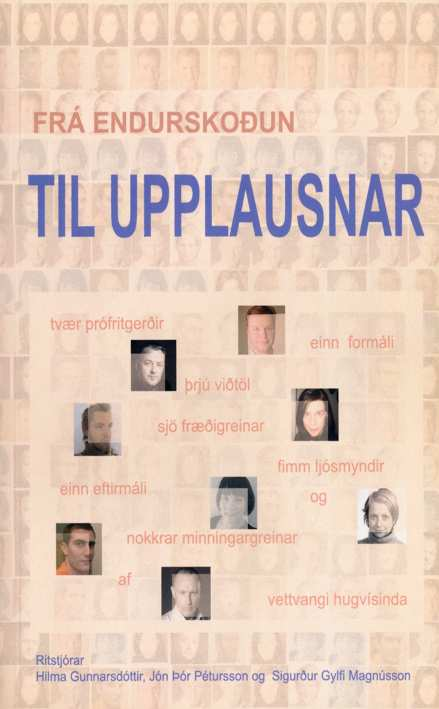

From Re-evaluation to Disintegration. Two Final Theses, One Introduction, Three Interviews, Seven Articles, Five Photographs, One Afterword and Few Abituaries from the Field of Humanities. The Nameless series. Edited by Hilma Gunnarsdóttir, Jón Þór Pétursson and Sigurður Gylfi Magnússon. Published by the Center for Microhistorical Research and the Reykjavik Academy, 2006. 444 pages. – (Frá endurskoðun til upplausnar. Tvær prófritgerðir, einn formáli, þrjú viðtöl, sjö fræðigreinar, fimm ljósmyndir, einn eftirmáli og nokkrar minningargreinar af vettvangi hugvísinda. Ritstjórar Hilma Gunnarsdóttir, Jón Þór Pétursson og Sigurður Gylfi Magnússon (Reykjavík: Miðstöð einsögurannsókna og ReykjavíkurAkademían, 2006)).

From Re-evaluation to Disintegration. Two Final Theses, One Introduction, Three Interviews, Seven Articles, Five Photographs, One Afterword and Few Abituaries from the Field of Humanities. The Nameless series. Edited by Hilma Gunnarsdóttir, Jón Þór Pétursson and Sigurður Gylfi Magnússon. Published by the Center for Microhistorical Research and the Reykjavik Academy, 2006. 444 pages. – (Frá endurskoðun til upplausnar. Tvær prófritgerðir, einn formáli, þrjú viðtöl, sjö fræðigreinar, fimm ljósmyndir, einn eftirmáli og nokkrar minningargreinar af vettvangi hugvísinda. Ritstjórar Hilma Gunnarsdóttir, Jón Þór Pétursson og Sigurður Gylfi Magnússon (Reykjavík: Miðstöð einsögurannsókna og ReykjavíkurAkademían, 2006)).

Preface

On the anniversary of universal suffrage in Iceland.

In 1972 the University of Iceland Institute of History launched a new series of monographs under the title Studia Historica. The first volume in the series was by Gunnar Karlsson, later professor of history at the university, under the title From re-evaluation to Valtýrism (Frá endurskoðun til valtýsku – “Valtýrism” being a political movement around 1900 that advocated compromise with the Danish colonial authorities). Gunnar Karlsson’s book dealt with one of the key stages in the Icelanders’ struggle for national independence – itself the dominant issue of modern Icelandic political history – at a time when a fierce debate was going on among the campaigners on how best to forward their aims. The book was thus written in the spirit of traditional political history, according to the dominant model among Icelandic historians at the time. The title of the volume published here makes direct reference to Gunnar Karlsson’s book. Thirty-five years have passed since Karlsson wrote and a lot of water has passed under the bridge within the world of the humanities.

The people behind the present volume seek to address another kind of re-evaluation, namely that which resulted from the “reshuffling” of the intellectual frames of reference around 1980 and went on to revolutionize the ways in which many scholars conducted their research. The ferment that took place in the last decade of the 20th century – in response to the re-evaluation of history that had come to dominate the world of historical studies in Iceland – not only called for a change in assumptions and methods but also dug away at the foundations of the institutional forms used in academic articles in the humanities and social sciences. The changes consisted of a disintegration – a breaking down – of received values in scholarship and the sciences. The history of this process is traced from the differing perspectives of twelve scholars from the humanities and social sciences.

In January 2003 I was approached by Hilma Gunnarsdóttir who asked me whether I would supervise her work on her BA dissertation. Hilma was interested in looking into some aspect of the theory and ideology of historical studies and over the next weeks and months we tossed a number of ideas back and forth between us on subjects that seemed worth looking into. I took considerable personal interest in Hilma’s proposal, knowing that it would be highly demanding and aware that since the founding of the History Department there had been only three BA dissertations dedicated to ideological and methodological matters. Coincidental with this I was working on a number of articles dealing with the state of historiography in Iceland and abroad and this seemed an excellent opportunity to have serious and systematic discussions on this area of my research with one of my students. As we got further into the year 2003 Hilma decided to do her essay on the re-evaluation of history in Iceland. She had been struck by the fact that this term had been very little in evidence in recent years and scholars who mentioned it in their writings were few and far between. For example, the term was referred to nowhere in the influential “millennium edition” of the journal Saga (“History”) which contained a scholarly overview by the leading historians in Iceland, including most of the professors at the university, of the state and status of the subject in the 20th century.

Hilma launched into her project with considerable energy and little by little it began to take on an interesting shape. We discussed the ins and outs of the material she was working on and in its final form the essay became, as it were, a kind of attempt to define the important phenomenon that the Icelandic re-evaluation of history indubitably is. To focus attention on the special status of this Icelandic re-evaluation of history Hilma had to look in some depth at the foundations that underlay the so-called “new social history” of the 1970s and 1980s. The project proved very wide-ranging and demanding but the outcome was marked by a rare quality and richness of ideas. Hilma sought her material from, among others, the work of the most prominent historians from the field of Icelandic studies during the 1980s, notably professors Gísli Gunnarsson, Guðmundur Hálfdanarson, Gunnar Karlsson and Loftur Guttormsson, and conducted extensive interviews with each of them in turn. These interviews are published here in the book with the kind permission of the interviewees, with the exception of Guðmundur Hálfdanarson, who chose not to have his interview recorded in print. These interviews without any doubt contain some of the most interesting comments to have appeared on Icelandic historiography in recent years and I wish to take the opportunity to thank these colleagues for giving other historians an insight into their ideas and thinking on the development of historical studies over the last quarter of a century: they are of enormous value to anyone interested in achieving an understanding of the ideological upheavals of the second half of the 20th century.

At the same time as Hilma Gunnarsdóttir was working on her dissertation another of my students from the History Department, Jón Þór Pétursson, approached me and asked me whether he could pick my brains for ideas on material for his BA dissertation. Jón had decided to do his essay for Eggert Þór Bernharðsson, appointed part-time lecturer in history at the University of Iceland, on the controversial documentary series Þjóð í hlekkjum hugarfarsins (A Nation Enslaved by its Mentality) made by the Baldur Hermannsson for Icelandic National Television and first screened in 1994. Originally Jón Þór had intended to discuss the subject from a cinematographic point of view but by the time we met he had started to become more interested in the ideological and methodological background to the film. The upshot was that Eggert Þór and I became co-supervisors of Jón Þór’s dissertation.

The collaboration here led to Jón Þór deciding in the summer of 2004 to join the Reykjavík Academy and in the autumn of the same year he moved into an office in the premises with Hilma Gunnarsdóttir and three other of my students. Hilma had joined the Academy in autumn 2003 along with Guðný Hallgrímsdóttir and Sigríður Bachmann, both of them MA students in history at the university. Hilma completed her dissertation in January 2004, and around the same time as Jón Þór moved in with Hilma, Guðný and Sigríður, another of my students, Magnús Þór Snæbjörnsson, joined the group. This group, or a part of it, has come to be associated with the web journal Kviksaga and formed a history cell that has taken a particular interest in methods and ideas in the humanities up to the present day. The members spent much of their time together, holding a lot of informal discussions, writing for the journal Kistan edited by Hilma and Jón Þór since early 2005, and for Kviksaga, the brainchild of these two together with Magnús Þór. We all got together regularly for meetings and discussions about books and papers we felt merited particular attention within the world of scholarship. I think I can safely say that these conditions proved highly conducive and stimulating for people wishing to discuss matters close to their interests and take on challenging projects within the humanities. These conversations formed part of the impetus behind the creation of this book.

Jón Þór completed his BA dissertation in the spring of 2005 and it proved an illuminating critique of the state of historical studies in the year 1993, the time when the documentaries were attracting most public discussion in Iceland. Jón Þór applied the methods of microhistory to analyze in close detail the main arguments put forward by historians, the general public and farmers’ representatives when expressing their views in the heat of the moment. By deconstructing the discourse Jón Þór succeeded in bringing out certain salient features of Icelandic historiography as manifested in the language used by various prominent scholars in the wider discussion of the programs. In fact, the essay went beyond this: in a highly arresting way it bridged the gap between, on the one hand, Hilma Gunnarsdóttir’s research and her discussion of the procedures and ideology of the re-evaluation of Icelandic history and, on the other, my own criticism of the historical establishment published in the journal Saga in spring 2003 in an article entitled “Aðferð í uppnámi” (Method in Turmoil). Both Hilma and Jón Þór were important contributors to the discussions among the group that constituted the west wing of the Reykjavík Academy since their work provided the impetus for a stimulating exchange of views on the many and various problems history has had to face in ever-increasing measure in recent years. “What is Icelandic history really about?” was in fact one of the questions that came up for frequent discussion at the group’s weekly meetings held between January and May 2005. From here the talk turned to the nature of history in general. Alongside their major contributions to the discussions, Hilma and Jón Þór found their own ideas coming into shape as a result of the scholarly synergy that built up within the group.

I soon decided to try and see to getting their essays published in some form or another. Work on this began just before the end of 2003 with their assistance. As mentioned earlier, it was a rare thing to be supervising two BA dissertations where the center of interest lay in historical ideology and methodology. There were also others in the West Wing discussion group who were working only similar lines on subjects related to these areas. So it seemed worth doing more than simply publishing my students’ two dissertations; I felt this was an excellent opportunity to bring in other people from the world of scholarship who were thinking about the future of the humanities and social sciences and were prepared to give serious thought to the possibilities that appeared to be opening up with the disintegration of scholarship and society. So we set about tracking down people we reckoned might have something to contribute along these lines. The fruits of this appear in part in this book.

In Autumn 2003, together with the literary specialists Þröstur Helgason and Eiríkur Guðmundsson, I taught a MA course for the Icelandic Department at the University with the title “Biographies – autobiographies – novels”. We had had to take on this course at short notice in the absence through illness of the original teacher, Matthías Víðar Sæmundsson, an illness that subsequently led to his death. The teaching gave me a welcome opportunity to discuss my ideas on life writing, a subject I working on at the time. One of the students, Guðrún Lára Pétursdóttir, produced an essay on the formation of the self that attracted my interest. I suggested she continue working on it and submit it for inclusion in the proposed collection, which she agreed to immediately. Her essay is an immensely thought-provoking ideological consideration of how the individual shapes his own self. The actual subject is Steingrímur Hermannsson, former prime minister and chairman of the Progressive Party, and the semi-autobiography of him published by Dagur B. Eggertsson in 1998-9. Guðrún Lára came to the conclusion that Steingrímur had applied unconventional methods in the shaping of his own self-image, taking a route deeply influenced by the prototype of his father – the prime minister Hermann Jónasson. The main focus of the article is on the interplay between father and son, and also with Steingrímur’s own son – how power is transferred between generations – providing Guðrún Lára with the opportunity to consider an unusual approach to the shaping of the self.

During the first part of 2004 the group formed that eventually worked together on the publication of the book. All are former students of mine and/or colleagues from the Reykjavík Academy. Among the former are Sigrún Sigurðardóttir, cultural historian, Jósef Gunnar Sigþórsson, historian and literary critic, Davíð Ólafsson, historian, and Guðrún Lára Pétursdóttir, literary historian; among the latter is Valdimar Tr. Hafstein, ethnologist and historian of culture. Valdimar, for instance, was co-editor, along with the historian and anthropologist Ólafur Rastrick, of the book Molar og mygla(“Pieces and Molds”) to which Davíð, Sigrún and I contributed – Davíð and I with articles and Sigrún, together with her husband, the philosopher Björn Þorsteinsson, as translator of a famous article by the microhistorian Carlo Ginzburg. I have had many and various rewarding dealings with Valdimar over the years, particularly during his long residency at the Reykjavík Academy prior to his recent award of a lectureship in ethnology at the University of Iceland.

As mentioned earlier, the group selected itself on the basis of its previous writings and its ideological explorations in various areas of scholarship. It is, without question, a group of inquiring and adventurous minds that has no hesitation in treading new paths in its research and working approaches. In a sense I see the scholars who are publishing their work here as representatives for all those who refuse to allow themselves to be pigeon-holed according to discrete areas of scholarship, people who challenge received attitudes within their disciplines and are ready to seek out unconventional ideas in their research. The fields represented here include history, microhistory, literary studies, anthropology, cultural studies, Icelandic studies and ethnology, but linking all the contributors is an approach that owes much to the ideas associated with postmodernism or poststructuralism – each in their own way and in differing measure. In this sense the group is treading a very different path from what we find in the vast majority of cases among scholars from the same disciplines. Many members of the group exhibit strong influences from the work of the microhistorians, who have taken experimentation in form further than almost anyone else in history in recent years.

Davíð Ólafsson’s article looks at the work of three well-know scholars in field of the humanities who have applied the methods of deconstruction in interesting ways. Critics of poststructuralism in this country have sometimes maintained that the number of scholars who subscribe to these ideas is relatively few and that there are even fewer who work according to their precepts. The idea seems to be that this is just a small bunch of disparate eccentrics in the field of cultural studies! In his article Davíð highlights three internationally known British historians – Keith Jenkins, Alun Munslow and Beverley Southgate – and shows that there is nothing to fear; people can take poststructuralism seriously and still hold their heads high. More than this, he succeeds in bringing out the possibilities that emerge from the ideas of these scholars to write history in interesting ways.

Valdimar Tr. Hafstein grapples with the concept of culture and shows how people’s consumption of culture influences their perceptions of the past: how the present works with history and culture in order to satisfy the demands made of what has gone before. Valdimar subverts the “sanctity” of the cultural heritage, showing it to be the product of the demands of the present, becoming as a result a symbol for everything and nothing. The area of study Valdimar is working with links in with the research into memory of recent years, which has served to direct people’s attention to the personal testimony of individuals and their position in the world. This testimony has contributed to the breakdown of traditional ideologies within the sciences and allowed us to observe the “manufacture” of historical perspectives in contemporary culture – the very area Valdimar Tr. Hafstein is dealing with in this book.

One of the most influential areas of research at the present moment concerns the ideology of what has been called postcolonialism. This is a perspective that has revolutionized people’s thinking about scholarship and the sciences, particularly by casting a light on the problems inherent in the Eurocentric view of history. This especially concerns work on subjects related to former colonies of the European nations and the attempts needed to find a common research interface between violently differing cultural worlds. The term sometimes used in this context is “postcolonial studies”, where the object of the research is to identify the consequences wrought by the policies of Western countries on the cultures and societies of peoples subjected to their colonial overlordship. The pioneer in this area is Edward Said, whose book Orientalism (1991) has had an enormous influence on how scholars approach the cultural status of areas that were formerly colonies. The term postcolonialism has been used in connection with the political, cultural and linguistic experience of peoples from countries formerly ruled by European powers. The subjects for study in this area are endlessly varied but are linked by having come strongly under the influence of poststructuralism.

The development of this area of research is treated briefly in my second article in the book, postcolonial studies having played a significant part in how scholarship is practiced at a time of considerable upheaval. With some justification one might say that the subjects treated by Davíð Ólafsson and Valdimar Tr. Hafstein have come under heavy influence from postcolonial thinking, although such influences are not conspicuous in their particular treatments. Postcolonialism has in fact had considerable indirect influence on the thinking of many scholars in Western countries who have struggled with the disintegration of scholarly frames of reference and have striven to manifest modern perspectives of discourse within the academic community. It is very likely that this area of research will go on to have a deep influence on Icelandic historians to come – once the door has been opened – and it seems certain that the thinking behind postcolonialism will change the ideas of those who make use of the methods of deconstruction in their studies. As said earlier, I believe we are already seeing signs of this in some of the pieces published here, among them the article by the cultural critic and historian Sigrún Sigurðardóttir, even if she is not working specifically on the basis of this ideology.

Sigrún’s article attempts to articulate how scholars can work with the perception of reality in their research, how the spheres of thought and emotion, which historians have largely left untouched, can have considerable significance for contemporary people’s ideas of reality. In other words, Sigrún is making an attempt to get historians to take account of dimensions in the conceptual life of mankind that many scholars have seen as irrelevant to their purposes. In her article she takes an unequivocal stance against the kind of postmodernism that views experience as being invariably bound up with language. To move away from this position she places the emphasis on the concept of trauma, requiring people to look at life in an entirely new way and approach reality independent of language.

Sigrún constructs her argument upon a long tradition of discourse with its origins in literary studies, philosophy and the arts and sets out to identify the signification of the ideas in contemporary life. She discusses the approaches she considers viable here and looks into the possibilities of new realism, which sets out expressly to handle phenomena that cannot be directly weighed or measured but which humans know perfectly well from their experiential world and encounter regularly through their emotions. It is precisely these kinds of indefinite and intangible concepts that Sigrún attempts to apprehend, maintaining that they can open up an unconventional ways of addressing important questions of the present time surrounding seminal events such as genocide and ethnic cleansing.

In a number of recent writings Jósef Gunnar Sigþórsson has set out to introduce historians to certain ideas developed in the field of literary studies under the banner of reception theory and show how they can affect our analysis of various phenomena of the past. In his article in the present volume he goes a step further and considers his own position in the world of scholarship using an approach grounded in reception theory. The article is a kind of calling to account in which he looks across the scholarly canvas and assesses ideas, methods and the academic community as he has encountered them both as a student at the University of Iceland and as a graduate now working in a completely different area of life. Jósef Gunnar’s article is particularly interesting in view of his position as a young scholar, like Hilma and Jón Þór, taking his first steps within the discipline and, I would maintain, the work of all of them evidences a new perspective on scholarship and its concerns. Jósef Gunnar’s position is the more unusual in that he stands unequivocally outside the academic world, working as a stonemason in daily life. This allows him a genuinely unconventional perspective on the academic community, though he maintains close contacts with it as an outside observer.

In my article on Icelandic historiography 1980-2005 I argue that the new approach among younger students in the humanities constitutes an important and unique juncture in the fourth wave of historical re-evaluation. In the article I set out to analyze the different intellectual waves within Icelandic historiography with a view to showing how the subject has developed so far and the salient features of the re-evaluation of history. This analysis builds upon the findings of Hilma and Jón Þór, as well as on older writings of my own. I try to show how currents and movements in history in Iceland have been shaped over the last quarter of a century so as to be able to assess the current state of the discipline and compare it with what has gone on in other countries. The article includes an extensive appendix listing reference works published in Iceland over the same period, since it is part of my thesis that the idea of narrative synthesis – the “broad brush approach” – has played a greater part in shaping Icelandic historiography than is healthy. The fourth wave of Icelandic historical studies, for which Jósef Gunnar, Hilma and Jón Þór stand as representatives, will in all likelihood adopt a quite different position towards the Icelandic historical establishment than the generation that preceded it, the one that constituted the third wave and learned its trade from the pioneers of the Icelandic revision of history. For complex scientific-political reasons touched on by Jósef Gunnar in his article, the fourth wave is largely free from institutional links – which I maintain in my article have constrained part of the third wave and left their mark on the scholarly approach of the majority of those who belong to it. The looser connections of the fourth wave with the institutions of history without doubt allow it a notable scholarly breadth and freedom that comes out in various of the writings by younger scholars in this book. However, as I see it, it remains to be seen whether the scholars who constitute fourth wave will live up to their promise and succeed in setting their mark on the world of scholarship.

My article on history in Iceland in the last 25 years opens the second part of the book, dealing with the disintegration within the humanities. The final article in the same section is also by me and discusses the idea of “singularization” that I presented in the book Molar og mygla in 2000. The “singularization of history” can be viewed as a kind of application of the ideology of microhistory and is based on the idea that it is essential, on all occasions, to sever knee-jerk, automatic links between the matter in hand and larger wholes. In the article I introduce a new approach to this idea linking in with the Slow Movement, something that has made a appearance in various areas of human life, such as architecture, cookery, and popular art, and in people’s everyday lives as a means of counterbalancing various paradoxical features of contemporary culture. My discussion is set within the context of present-day concerns – globalization, the internet, the opening up of markets – and I consider the various means that are likely to offer themselves for exploiting the opportunities presented by the disintegration, including on the basis of the ideology of postcolonialism.

Seen overall, the present book is conceived as a kind of protest – a dissenting voice – in an intellectual sense. It is directed against conventional scholarship and the spirit of all those within the academic community who allow themselves to pay only scant regard to the ways in which learning manages to develop. In recent years these people have adopted a posture of “ordinary citizens” impelled to glorify “great men” as they appear in the guise of political leaders past and present. What we find is the promotion of glossy images of certain individuals who have set out to guide the masses, wrapped up in a range of clever propaganda devices. For instance, the public authorities have been more than ready to put money into festivals, popular history and other events whose sole aim is to promote particular individuals who have stood at the forefront of national movements or parties – and the academic community has been happy enough to go along with this. Instead of protesting, raising objections at the fossilized images of the past that are held aloft in the interests of particular groups or individuals, a large part of the academic community – and particularly the historians within it – have jumped on the bandwagon as willing participants in stunts of this kind – with a debilitating effect on competition funds and the academic community.

This book is directed against the insipidness that such thinking engenders. It is an attempt to demonstrate that there are things that matter that are quite separate from politics and politicians (in the narrow sense of these words), and there is a pressing need to look for ways to find a place for scholarship within contemporary ideas on culture, power and education. Social historians have known for decades that politics simply do not matter and have adapted their research accordingly. Where their studies have led them into the realm of “politics” it has been treated as a “phenomenon”, as a sociological entity, rather than as a symbol of the greatness of individual men that interest groups strive to glorify in the style of some religious drama.

As readers of this book will discover from the pieces by Hilma, Jón Þór and myself, all the social historians in the country appear to have been roped in – the production of narrative synthese for general consumption is a hard taskmaster that permits no straying from the designated path. The process leads the participants to sit themselves at the feet of the great and the good because it is they, inevitably, who pay the bills. The production of summary history is expensive – the National Center for Cultural Heritage, the Home Rule anniversary celebrations, the Festival of Emigration to America, the celebrations of 1000 years of Christianity, the chronicle of prime ministers, the history of parliamentary democracy, of the government buildings and the bishoprics, to say nothing of the history of Iceland itself – all are projects that require an enormous outlay of funds that only the highest authorities are in the position to grant. The university professors collect round the trough and dash off one big job after another, with plenty more still waiting in line. Isn’t the 100th anniversary of the University of Iceland coming up soon? That’s an important project and someone needs to see to it. Maybe it’ll be enough just to set up some new memorial – some giant construction on the campus encompassing the various institutes of Icelandic studies.

The result is that intellectual currents from aboard are for the most part given short shrift; the power of science and scholarship to challenge and protest is muzzled in a community of interests between the educated elite and those in power, and everyone dreams of wittering on about “the loves and fates” of the great figures of politics, past and present.

The book that follows declares war on those who perpetrate this way of thinking. We seek to break the history of scholarship in recent years – particularly history – down to its basic elements and look to the future with an eye to dissolving the received perspectives that have shaped the humanities over the last decades. In the postscript to the book we the editors present one small example of how this kind of breaking down – this protest – can be done, by directing attention at the unconventional experiments of the anthropologist and poet, Tryggvi V. Líndal, to get his ideas across in the public arena. A few years back Tryggvi came to the conclusion that all opportunities for open discussion in the newspapers had dried up, and that the only means left to him to express his ideas and poetry was to avail himself of the forum offered by the obituaries column. Tryggvi is a genuinely driven crusader, someone who refuses to back down in the face of overwhelming odds and does not hesitate to use unconventional methods to do so. People within the halls of academia have much to learn from Tryggvi’s “assault” on the form, this breaking down of tradition and refusal to accept the trite and the obvious, the face of received wisdom and practice.

We have looked to a number of individuals for technical assistance in bringing this project to fruition. We wish to thank: Ásdís B. Stefánsdóttir, proofreader; Ragnhildur Stefánsdóttir, sculptor; Ingólfur Júlíusson, photographer for the cover design; and Sverrir Sveinsson, printer, who saw to the layout. All these people have performed their tasks with great professionalism and attention to detail. Representatives of the Reykjavík Academy agreed to act as co-publishers alongside the Center for Microhistorical Research. The second of these is now actively involved in a number of projects in the arts and sciences that will hopefully be stimulated by a new database recently set up on the web under the title microhistory.org. I wish to thank all those who have played a part in the production of this book – authors, designers, printer, proofreader, readers of various articles and last but not least my co-editors and friends, Hilma Gunnarsdóttir and Jón Þór Pétursson, for particularly enjoyable and rewarding collaboration over the last years.

Please note that full bibliographic details of articles, books and other material is given at the point where they are first mentioned; thereafter truncated references are used. The list of sources at the end of the book covers all the articles appearing in it.

The authors in this book, each in their own way, discuss the concept of disintegration and the opportunities it has to offer historians and others wishing to take on research projects in the future. One thing that unites us all is the desire to demonstrate the possibilities for growth of the new ideas that are taking shape within contemporary culture.

On the 72nd anniversary of universal suffrage in Iceland, 24 March 2006.