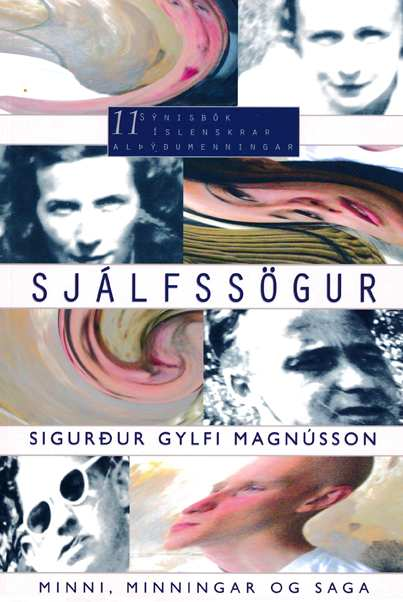

Metastories: Memory, Recollection, and History. Anthology from Icelandic Popular Culture 11. Published by the Icelandic University Press, 2005. 429 pages. – (Sjálfssögur. Minni, minningar og saga. Gestaritstjóri Soffía Auður Birgisdóttir. Sýnisbók íslenskrar alþýðumenningar 11 (Reykjavík: Háskólaútgáfan, 2005)).

Metastories: Memory, Recollection, and History. Anthology from Icelandic Popular Culture 11. Published by the Icelandic University Press, 2005. 429 pages. – (Sjálfssögur. Minni, minningar og saga. Gestaritstjóri Soffía Auður Birgisdóttir. Sýnisbók íslenskrar alþýðumenningar 11 (Reykjavík: Háskólaútgáfan, 2005)).

The boundaries between truth and lies, which appear at times to have been obliterated, have influenced both people’s conceptions of reality and virtual reality and their understandings of their own selves. How is it possible to work towards an integrated image of one’s self when everything appears to be in flux? Without trying to offer any kind of definitive solution, I have attempted in this book to direct attention on the sensitive relationship between man and his environment and how this effects the shaping of people’s ideas about life and existence. At times people will go to extraordinary lengths to put their own vision of society across – a vision that may be contaminated by political chauvinism and a conscious travesty of reality – and offer it to readers under the guise of ‘truth’. It is salutary to remember a recent case in which various influential figures from Icelandic politics chose to defend the treatment and methods used by the author of a biography of the Nobel laureate, the novelist Halldór Laxness, methods that were patently based on lies and deception, viz. plagiarism. The author in question was, of course, a professor of the university, with connections reaching into the innermost core of the power élite of Icelandic society, and this was a state of affairs that could not be allowed to go undefended. There has been some discussion of how such cases impact on technical practice within academia – how students should be taught to treat sources in the light of these kinds of things – but less has been said about the ethical problems thrown up in this connection.

In this book I take the view that man is not one but many, that it is impossible to present a picture of a person as a single coherent entity that endures through the course of its life circumscribed and signposted by the sites of memory. The same applies to knowledge and scholarship: they cannot be treated as an integrated and permanent logical representation of reality; quite the opposite, they have to acknowledge and accept the oppositions and contradictions that present themselves in every case, with every ‘truth’.

By accepting the multifaceted natures of mankind and learning we open up for ourselves ways of talking about the past in a far more exciting way than was previously possible. The perspectives become numberless and the voices that get to ring out uncountable. But this is not all: not only does the number of individuals that manage to emerge from the shadows and appear in their own right increase, but we also get the opportunity to bring out the varied approach of each individual in his own right when discussing society at any period and to present every person as an composite of many beings.

In this book I trace the forces that have shaped self-expression in Iceland over the course of the centuries and show how traditional debate has encouraged a particular understanding of this development. Scholars’ ideas about the self and its creation have been greatly influenced by ‘Modernization Theory’. But other grand narratives have also played their part in this: Romanticism, for instance, was instrumental in shaping Icelanders’ ideas about the ancient literature of their country, and this in turn had a powerful influence on how individuals chose to direct their lives. The form in which the memories were cast proved to be a major factor in how individuals experienced the course of their own lives.

The individual in word is not the same as the individual in deed. Between these two poles lies a gulf that can never be bridged. For most of the 20th century scholars have taken as axiomatic that the testimony of individuals when speaking about their own selves is irredeemably flawed and worthless for work with any kind of scientific purpose in mind, while acting as if completely different laws applied to the supposedly ‘objective’ expression found in public sources of past events. Considerable energy has been expended in demonstrating that there is no way of using personal sources without sacrificing all claims to academic standards and principles. In this book I suggest that the only way to counter the attitudes of traditional historiography is to work systematically with the sources and break them down into their fundamental units. In order to do this, I attempt to classify ‘life writing’ into distinct groups on the basis of the impetus that appears to have lain behind the writing of each work. The results of this discussion bring to light a particular trend of development within life writing which provides some genuine illumination of the situation of individuals in modern societies. As part of this I believe I feel it is worth going over the changes that self-expression has undergone between the 18th and 21st centuries, while stressing that what I am dealing with here is a conjecture based on the research behind the book.

One of the most powerful influences here has been gender studies, which have wrought major changes to how life writing has been handled within the world of scholarship. People’s ideas about the workings of memory and its connections with recorded recollections have also encouraged a more varied use of sources that arise directly from people’s personal expression of their own lives. The present age has allowed us to hear voices that previously would have remained unheard because a particular ideology did not see them as serving its cause. Research into memory has thus revolutionized the status of life writing and strengthened people’s faith in the value of memories as a channel for relaying their lives, for giving them a voice. In the atmosphere of the cold war, those who were permitted to present themselves to the public at large were selected along particular ideological lines (the grand narratives). Now, in the present, everything is possible. We have achieved meltdown!

On the basis of my research it appears that the authors of the vast majority of books written by women and classified as life writing tend to avoid the self. The writers make a conscious attempt to absent themselves from their own narratives. In this I go along with other scholars who have looked in greatest depth into Icelandic women’s autobiographies. Where I differ from the analyses of these critics is that, as I see it, this is also one of the chief characteristics of autobiographies written by men who were born in the 19th century and the earliest years of the 20th. They manage to talk about themselves and their lives’ work in a way that gives the reader the impression that they are the center of the narrative, just as happens with many women’s autobiographies, while in reality employing a narrative technique based on an attempt to objectify everyone who comes into the story, themselves included. In order to do this, they need first to create a distance between themselves and what is being described. Exactly the same is true of the accounts written by women; they hold themselves outside their own lives and look at them from a distance, appearing for all the world to be describing extraneous objects from their own existence. As I see it, this is one of the most salient features of all autobiographies at this time. This is the period that is most strongly marked by what I have called ‘the culture of testimony’; it is the period when the writers’ main concern was to testify to their own part in the shaping of the nation or other collective undertakings, when people viewed themselves as one part of a greater whole working towards a common goal, viz. that of making Iceland a sovereign nation. It seems to me that the great majority of these autobiographical authors, both men and women, experienced difficulties stepping outside this framework and into their own selves. The centrality and visibility of the self of course varies between individual works, but as a rule it is simply not the main concern in these works. In my view, what matters more is to recognize that the self is being objectified, that it is being treated as a topic within a greater context where authors are providing testimony at their own trials of themselves and their society. For this there are, I believe, particular explanations that can be inferred from a general development within autobiographical writing and that it is important to treat as a special subject for discussion.

As mentioned previously, Iceland is somewhat anomalous as regards people’s associations with memory in the 19th century. As I see it, the collective memory as I have defined it was exceptionally weak in Iceland. As a result of the geographical conditions groups found it difficult to coalesce within the kinds of bonds that were the prerequisite for sharing their memories and holding them in common. Even the group best placed to sustain their collective memory, viz. the educated, was dispersed among the ordinary people and absorbed the thought and activities of the agricultural community without being able to maintain its earlier links forged during schooling and education. In other words, the collective memory was so weak that extra space was available for the other two forms in which memory manifests itself. Thus individual memory was given much greater freedom to express itself than in most other parts of Europe. At the same time the position of historical memory was strong, especially in comparison to its rather weak position in other countries in the 19th century. The situation was thus this: Individuals had more latitude to shape their own memories, and this was buttressed by the historical memory with its direct links to the ancient culture of the Icelanders. Each of these types grew stronger and stronger through the course of the 19th century in parallel with the powerful arguments put forward by the leaders of the independence movement. In this, the ancient cultural world of Iceland, and above all the material of the family sagas, was used to create a national historical memory and an image of what was felt to be worth focussing on. However, despite this strength of the historical memory, the individual and his personal memory held its ground, because it was individuals that had to read and pass on the historical memory to the groups to which they belonged and who thus became an important nexus between history and other individuals. Memory was thus built up upon the living experience of individuals, for whom there was no way of avoiding coming to terms with the historical memory. This perhaps suggests a reason why autobiography became a more widespread form of expression in Iceland that in most other parts of Europe.

In the book I consider the question of whether people in Iceland have had the confidence to look at their own selves face to face and to what extent society has offered them the opportunities to do this. It is possible to answer this in various ways, but one thing is certain, that as things stand nowadays people are explicitly encouraged to ‘open’ themselves up in the public arena. Those behind ‘the Emotional Square’ promote meetings where people are urged to tell their own stories and receive support from others taking part. Thus a Reykjavík newspaper announces that a well-known writer will be ‘receiving guests on the Emotional Square, to be held at the restaurant Hressó [High Spirits] today between 2 p.m. and 5 p.m.’ It is clearly appropriate to conduct a meeting of this kind at this particular eating place, especially as such events are intended as therapy, i.e. to lift the spirits, for those who put themselves forward to air their problems in public. ‘On top of this, the artist Steinunn Helgadóttir is going to sell feelings, and all feelings will be on sale,’ as the newspaper announcement goes on to say. What follows in the article suggests that those behind the event are by no mean entirely tongue in cheek about themselves and their project, since we hear that Steinunn will be offering ‘among other things genuine feelings, and they are more expensive that other feelings and are sold singly.’

Events of this kind fall under what I term ‘the culture of confession’, in which people put themselves forward in public to tell their stories to other people. But although this kind of expression appears to be much more open than that which went on within the bounds of ‘the culture of testimony’, it should never be forgotten that both are narrative forms which give shape to people’s thoughts and actions – a genuine rhetoric.

In this connection one may ask, how do thoughts come into existence? and how do people remember their lives or the events connected with them? In the book I look in some detail at how commentators have talked about memory and people’s ideas about existence. It is interesting to consider the interplay between the collective memory and the historical memory, in which the former determines the construction that smaller groups put upon the events and activities that connect its individual members together. Memories of this kind are supposed to have lost their significance in the complex societies of the modern age, once the traditional groupings, such as village communities, started to break down. They were superseded by the historical memory, which was a construct of specialists whose job it was to ‘create’ memories seen as being of importance. The complex process of memory production was long viewed as have ‘disengaged’ people from their own memories; such memories existed only in so far as they fitted in with the historical memory. This meant, for example, that at the time of ‘the culture of testimony’, which was a manifestation of the historical memory, there was little scope for narratives that reached outside the framework imposed by the form of testimony. Accounts of journey into hell, of death camps and gulags, were not believed if they were aired at all, and for this reason it was felt reasonable to subject individuals who expressed them to all kinds of force and compulsion. Within the narrative tradition such phenomena simply did not exist! The historical memory in this sense was a stern master with a tyranny constructed on the landmarks of memory, signposts that told people how they should live their lives and what was to be taken as important when doing so.

The problem with the understanding of memory production outlined above is that it denies the individual any input into his own fate. In the book I show that this does not necessarily need to be the case, since the sites of memory, like in fact the historical memory as a whole, are frozen and fossilized images of the reality; they are templates that lock people’s minds onto the idea that lies behind them, but the ideas about the historical memory build equally on the idea that they are to be interpreted and explained through individuals’ experience of them. In other words, they are, when all is said and done, molded and interpreted on the basis of personal experience and so take on an entirely new life in the minds of individuals. Through this approach to the concepts of memory the individual becomes a considerably more active participant in his own life, since he reads the historical memory and interprets it on the basis of countless perspectives from within his own life. Seen this way, it is necessary to bolster and reinforce those conditions within society that provide people with opportunities to come to their own conclusions about life and existence. There are of course always forces ready to grasp any opportunity to control the historical memory in the hope that this will then enable them to influence how it is received. Over this there is competition in various areas of society and at all times.

Scholars have applied different concepts of memory to pin down the nature of the struggle that frequently prevails between different forces. Research of this kind has sharpened people’s awareness of the effectiveness of their own lives and the possibilities for expression that are available to them.

This process of deconstruction indisputably involves a heterogeneity and thus creates certain dangers. The structures that held expression together – in orbit around specific ideas – are breaking up, creating a certain dissolution. This is something to be welcomed in that it allows different viewpoints easier access to the present. We can clearly observe this happening in autobiographical expression; such expression has grown exponentially and gained strength with every passing year and now forms part of the general communication process of societies. But with this dissolution comes a certain responsibility that has to be borne by those who put themselves forward. This responsibility is shouldered in a variety of ways in society, whether by private companies, the public authorities or individuals.

The book contains definitions of all the main concepts used in it, a little over 200 in total. It is my great hope that this glossary of concepts may act as a kind of manifesto of how I envisage the past and how historians can approach it. In this connection, it is my belief that people’s understanding of history and the past must always come through their own knowledge and consciousness – their thought and imagination – and thus be part of individuals’ experience of what has gone before them.