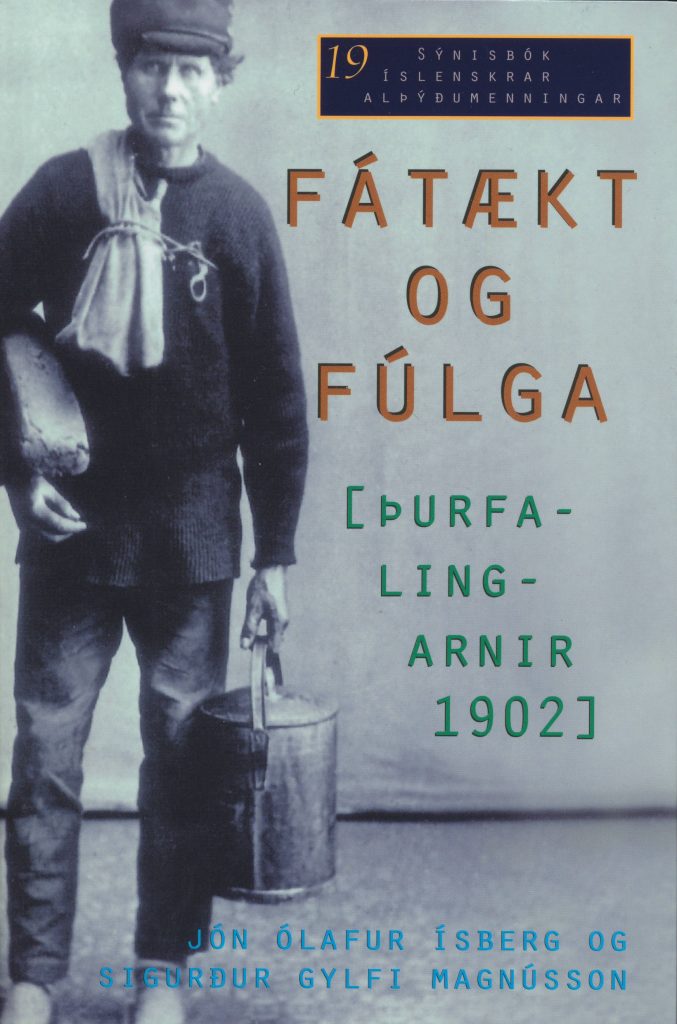

Penury and Poor Relief. Pauperdom in 1902. Anthology from Icelandic Popular Culture 19. Co-author Jón Ólafur Ísberg. Published by the University of Iceland Press, 2016. 429 pages – (Fátækt og fúlga. Þurfalingarnir 1902. Sýnisbók íslenskrar alþýðumenningar 19 (Reykjavík: The Center for Microhistorical Research and the University of Iceland Press, 2016).

Penury and Poor Relief. Pauperdom in 1902. Anthology from Icelandic Popular Culture 19. Co-author Jón Ólafur Ísberg. Published by the University of Iceland Press, 2016. 429 pages – (Fátækt og fúlga. Þurfalingarnir 1902. Sýnisbók íslenskrar alþýðumenningar 19 (Reykjavík: The Center for Microhistorical Research and the University of Iceland Press, 2016).

Poverty was a major issue in Icelandic society in the latter half of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth – and remains one today in the twenty-first. And there is nothing surprising about this: in the nineteenth century, poor relief consumed a huge proportion of local government funds in every community in the country, accounting for the vast majority of tax revenues. The manner in which poor relief should be provided was a matter of constant friction.

Historians have pointed out in their scrutiny of poverty that in the old agrarian society diligence and prudence were highly valued, with the expectation that people would shoulder their own responsibilities, living by farming on their patch of land. Nonetheless, from early times communities provided poor relief to those who could not support themselves due to illness, accident, natural conditions beyond their control or other setbacks. The agrarian society developed methods to reduce the risk and meet unexpected demands on resources, in a “social security” system of a kind. When a farming family suffered some setback, such as a fire or death of livestock, the local authorities stepped in to provide assistance, sometimes even raising contributions from the community.

Community councils often faced near-insurmountable problems. Examples are taken here of two women: one in her twenties, who embarked on a rootless wandering life, for no obvious reason. She seemed to be a quite ordinary Icelandic girl of her time. But, like so many poor people in Iceland at the time, she had been moved around repeatedly from one farm to another as a child. On her wanderings she had four children by four different fathers; all became wards of the authorities in her home district. She herself was repeatedly convicted of theft – often mere pilfering – for which she was sentenced to birching and even imprisonment. In the end no-one was willing to take her in, and so she was often sent from one farm to another, as the farmers took turns feeding and housing her. Her home community was faced with a problem that appeared to be impossible to resolve, as the woman herself determinedly refused to be managed. She lived into old age, and was thus a considerable burden on public funds.

The other example is of a women who lived a life of poverty and hard work. Despite her lowly social status she managed to a achieve a certain degree of security for much of her life. She was a diligent peasant woman, who was well known as a good worker and could always find employment. But she married a wastrel who squandered all their assets (mostly hers) after they had a child together. She separated from her husband, to find herself alone and penniless in middle age. Her later years were a difficult time, and in old age she was cast on the mercy of the authorities as a pauper.

We explore the lives of these two peasant women, who both found themselves looking to their local authorities for assistance. Their stories highlight the variable position of women in nineteenth-century rural Iceland, while also illustrating the difficulties faced by the authorities when dealing with individuals who did not fit into society’s preordained pattern. The nineteenth century abounds in such stories; and these individual tales are told in order to explore the problems faced by a society which was not only poor but also undeveloped in terms of infrastructure and social security.

As the nineteenth century progressed, new ideas emerged regarding poor relief, informed by international trends towards taking more account of the needs and position of poor people. The presumption was that poor people justly had a right to be able to live a decent life. Such ideas were introduced into Iceland predominantly by intellectuals who had studied in Copenhagen, and saw it as important for Icelanders to adopt new approaches to both education and poor relief. This group wrote extensively in the press in support of their ideas. Their argument was partly grounded in the principle that society as a whole must take some responsibility for its poorer members, who had few opportunities for gainful employment in the more-or-less stagnant Icelandic economy.

There were many, on the other hand, who stuck to their guns and refused to consider any changes to the system of poor relief. Some favored an even more stringent approach, rather than more liberal assistance; and this group was voluble and influential both in parliament (Alþingi) and in society in general. Such attitudes probably reflect unease over the changes which had already occurred in society, with the beginnings of urban development combined with mass emigration to the New World. These two elements had disrupted certain social norms which had hitherto been unquestioned. In the 1870s Icelandic farmers started selling sheep on the hoof to British buyers; for most this was the first time that they had ever had hard cash in their hands, as the old rural economy functioned mainly on barter and credit. With money in their hands, people were able to make changes in their lives and attain autonomy vis-à-vis the rigid social structure as cash entered the economy.

Among the upper classes, there was fear that the old values would be swept away – and hence a desire to make changes by small increments. While the concept of “progress” was widely accepted, in this book we maintain that the vast majority favored what has been called a “conditional progressive policy.” This was grounded in the idea that when changes were undertaken, no expense must be incurred. This widely-held proviso effectively stifled all the new ideas proposed by those who had studied abroad and learned about new international trends.

In this book we have sought to examine the lives of poor people from various perspectives. The public discourse on the subject has been discussed, and we have also become acquainted with the personal narratives of individuals who experienced poverty and hardship during their lives. This material draws on important autobiographical matter – egodocuments – written by Icelandic peasants in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. We have taken the innovative step of following up on such narratives by searching the inventories of household goods and chattels (uppskriftabækur) drawn up by district commissioners (sýslumenn), generally in connection with the distribution of estates or when poor households were broken up as a result of public debts. These inventories typically go into minute detail, cataloguing anything found in the household of even the slightest monetary value, and thus provide an invaluable insight into the everyday material lives of people at the time. It is safe to say that this approach opened up an entirely new perspective on matters of poverty: it reveals the aggressive measures applied by the authorities (men who were themselves farmers) in collecting debts to the local authority; and also the material poverty with which Icelanders in general lived. It is safe to say that the Icelandic peasantry lived in penury.

Data gathered in 1902 by a parliamentary committee on poor people in society, on which the analysis in this book is based, was a game-changer. It may be compared with the extensive data-gathering carried out at about the same time on primary education, and how it could best be provided: that same year the Alþingi enacted legislation based on the new information on educational issues. Following the collection of data on poverty, proposals were drawn up regarding life assurance for fishermen on schooners. These were enacted as law in 1903, marking an important landmark in the history of accident insurance in Iceland. The Kleppur psychiatric hospital in Reykjavík was founded in 1907 as a result of the committee’s proposals, as the investigations had revealed that a large proportion of the impoverished in society had mental problems. Pensions for the disabled/elderly were also among the proposals of the committee – or more precisely of its chair, Páll Briem; this was put into practice at the end of the first decade of the new century. The position of the elderly was also a recurrent theme in the papers submitted by local council leaders; and it was clear that action must be taken to make life easier for them in their twilight years. Hence the work of the committee may be said to have had importance in many different ways.

The aspect of the committee’s work that was regarded as most remarkable was the way that it had set out to gather information – in an effort acquire precise information yielding a reliable overview of this issue, which had so long been controversial. The documents submitted to the committee by local council leaders are published in the book – as they must be deemed some of the most vital primary sources in the history of the modern Icelandic state. While these documents do not tell the whole story of poverty and the poor, study of them yields enormously significant knowledge about the situation with regard to poverty in the early twentieth century. The council leaders’ notes and observations are a subject in themselves – in them they express their views on many of the impoverished people whom they had to deal with. Those observation are often very harsh.

In the discussion in the book we have sought to throw light on developments with regard to poverty from many different viewpoints. One of the questions we have sought to answer is whether poverty was a hereditary tendency. The documents show that this was regularly asserted in public discourse; and many of the measures applied were based on a fear of “welfare dependency”– the idea that children would grow up with no role models for supporting themselves, and would automatically rely on poor relief like their parents. And worst of all, such (hypothetical) children would see no shame in doing so.

The findings of our study, however, give no indication that poverty ran in families in any consistent way. This is because such a large proportion of Icelanders lived on the edge of poverty, fluctuating between self-sufficiency and setbacks which meant only one thing: poor relief, and dispersal of the family as paupers. Even a prosperous farmer risked losing everything if natural conditions were unfavorable for several consecutive years. But it is also clear that those who were classified as poor in the latter half of the nineteenth century could find it difficult to break out of the poverty trap, due to large families and unfavorable natural conditions for farming. As a result their children tended to fall into the hands of the authorities, and that often meant that they too entered upon a life of poverty like their parents. In that sense poverty may be said to have dogged certain families for decades at a time.

In the end, poverty may thus more accurately be seen as a curse on the nation as a whole, and not just on certain families.