Microhistory – Conflicting Paths. Eight Essays and One Sculpture. Sigurdur Gylfi Magnusson and Erla Hulda Halldordsottir, (eds.). Published by the Icelandic University Press, 1998. 247 pages. – (Einsagan – ólíkar leiðir. Átta ritgerðir og eitt myndlistarverk. Ritstjórar Sigurður Gylfi Magnússon og Erla Hulda Halldórsdóttir (Reykjavík: Háskólaútgáfan, 1998)).

Microhistory – Conflicting Paths. Eight Essays and One Sculpture. Sigurdur Gylfi Magnusson and Erla Hulda Halldordsottir, (eds.). Published by the Icelandic University Press, 1998. 247 pages. – (Einsagan – ólíkar leiðir. Átta ritgerðir og eitt myndlistarverk. Ritstjórar Sigurður Gylfi Magnússon og Erla Hulda Halldórsdóttir (Reykjavík: Háskólaútgáfan, 1998)).

Foreword: Maid Imba and her offspring

There was a story going around at the time when the spring 1997 issue of the literary journal Skírnir came out, that one of its readers had happened to glance at the cover and exclaimed: “Well there’s a nice and timely picture for the cover, what with the first Icelandic History Conference just about to start!” The picture that adorned the cover of this issue of Skírnir showed an old woman, seated in a chair with her knitting needles, completely taken up with her work in hand. The picture was the work of the artist Kristín Bernhöft (1879–1957) and the subject appears to have been a woman who went from house to house in Reykjavík doing knitting for people and who bore the nickname Maid Imba (Imba mey). In the mind of this particular reader, Maid Imba was a fitting image for a whole and healthy scholarly discipline. This comparison, remarkable in itself, ought to be cause for considerable uneasiness among all those with an active interest in history.

It seems as if history (Maid Imba) is barely, if at all, out of her traditional national dress, as regards both material and treatment. Her way has been to move along slowly, or better still to keep to her place, in marked contrast to her sisters elsewhere in the western world, who have walked tall and bold through the highways and byways, ready to take on anything that presents itself. There are of course honorable exceptions to this, but the remark of the Skírnir reader is at the very least indicative of other scholars’ attitudes to our Maid Imba. The first Icelandic History Conference mentioned earlier almost certainly consigned Maid Imba to her final resting place. There it became apparent, beyond any doubt, that history is taking on the progressive form of a scholarly discipline anxious to avail itself of all possible means to face up to a wide variety of subjects from the present and the past. Though relics of Maid Imba are still to be found all around us and her ghost pops out to haunt us from time to time, it is clear that there is no way back for her as an meaningful participant in the lives of mortal men.

The collection of articles published here under the title Einsagan – ólíkar leiðir (Microhistory – conflicting paths) provides yet further confirmation that a new age has dawned within the discipline. It includes articles both by young scholars taking their first steps on the foothills of history and by more experienced historians already with a body of work behind them in recent years. The volume is the fruits of a working group that met once a month over a year and a half, between January 1996 and May 1997, to discuss the significance and interpretation of personal sources for historians. From early on this group evinced signs of a determined effort to approach personal sources using the methods of what is known in the English-speaking world under the name of microhistory, and from this the group came to be known as Einsöguhópurinn (the Microhistory Group). The group consisted of some twenty scholars, most of them historians but also taking in a literary specialist, an Icelandicist and one or two others with varied professional backgrounds. What they all had in common was the use of personal sources in their research and an interest in expanding the use of such sources within the world of scholarship. Many were engaged in editing texts or writing degree dissertations and it is safe to say that all the members of the group gained considerably from each other’s help and support.

The articles in the book are all the product of this co-operation and the discussions that took place within the group. They are intended as an introduction to a number of interesting topics and innovative approaches. Readers will swiftly come to see, however, that older historical methods have by no means been thrown over board in this work; the emphasis is on blending the methods of traditional history with the new perspective of microhistory. The book is also witness to the variety of approach within microhistory to such diverse research topics as diary keeping and the conditions of foster-children. In the nature of things, subjects of these sorts call for methods that need to be adapted according to the material. In this book microhistory comes out as a common term encompassing a wide variety of approaches among historians to a wide range of topics.

The first article is the contribution of one of the book’s editors, Sigurður Gylfi Magnússon, who traces recent developments in social history in an essay entitled “Félagssagan fyrr og nú” (Social history, past and present). The main thrust of the article is to show how developments within social history led historians in many parts of the world to turn their attention to a particular methodology that has come to be known as microhistory. Sigurður Gylfi focuses chiefly on three different parts of the world and the different ways that social history has developed in each of these areas. In the English-speaking world this new research tradition has come to be known as grass-roots history, in Germany everyday history, and in Italy microhistory. Developments in these regions are compared and the author attempts to show that microhistory was in reality an “emergency landing” for many historians who found themselves dissatisfied with the prevailing general trends within social history. Sigurður Gylfi points out the radical nature of microhistory’s attempt to break free of the institutional history that has characterized social history and to shed light on topics that have hitherto attracted little notice. The article looks at the methodological advantages and shortcomings of microhistory and demonstrates a number of the ways in which it can be applied. The author believes that microhistory is still at a formative stage internationally and that Icelandic historians and others involved in social research can have a significant part to play in shaping its methods.

A number of the other articles center on methodology of microhistory. One of the characteristics of the work of those involved in microhistory is to be as precise as they can about the origins and form of the sources they use in their research. Davíð Ólafsson contributes a highly interesting article on the nature and development of diaries in Iceland under the title “Að skrá sína eigin tilveru” (Recording one’s own existence). His article in fact exemplifies the ways microhistorians have sought to bring out connections between sources and their environment. Davíð’s research marks a turning point in the use of personal sources, being the first attempt to analyze how diary keeping developed in Iceland and how widespread it was. The author associates the development of diary writing with changes that occurred early in the modern age in people’s ways of thinking, particularly as regards the position of the author in written works. Davíð has compiled a comprehensive inventory of all diaries preserved in the manuscript department of Landsbókasafnið Íslands – Háskólabókasafnið (the National Library/University Library of Iceland), a project that will revolutionize the ways in which these remarkable sources can be used. His conclusions are in many respects unexpected, since he manages to demonstrate a clear connection between the annals of former ages and the writing of diaries, a connection that had by no means been obvious before. His discussion reveals that the lines between traditional public sources and personal sources were extremely blurred in the early part of the modern age, a conclusion that necessitates a re-evaluation of how historians use these sources.

Sigrún Sigurðardóttir contributes an interesting article on microhistory and its links with postmodernism. She provides a thought-provoking discussion of how relativism can act as a tool for historians in their research. She shows that relativism does not of necessity lead historians into blind alleys but can act as a liberating agent against the external framework of society and the bounds that man is set in the past and the present. In this Sigrún diverges from most scholars who have embraced the methods of microhistory, since they have tended to take pains precisely to avoid allowing research based on this methodology to become enmeshed in the constrictions of relativism. Using examples from the collected letters of the children of Jón Borgfirðingur, Sigrún shows how they attempted to break free of the formal structure of society, while simultaneously being held securely within it. The conclusions are based on an extensive study of the personal papers of the family of Jón Borgfirðingur, taking in letters, autobiographies and narrative accounts. Sigrún does not hesitate to take unusual historical material and apply the methods of microhistory in disentangling and analyzing it. Her conclusions are challenging and suggestive of many other ways that analogous subjects might be handled.

The last methodological essay in the book is by Jón Aðalsteinn Bergsveinsson and bears the title “Allt lífið, öll tilveran er órekjandi vefur: um sjálfsævisögu Matthíasar Jochumssonar” (All life, all existence, is a traceless web: on the autobiography of [the poet] Matthías Jochumsson). The article deals with the origins of this important autobiography, its textual history and Matthías’s own links with the western cultural world. The importance of the article lies in its examination of how autobiographies come into existence, and autobiographies are without doubt one of our most important groups of personal sources. Matthías’s autobiography is not only among the most accomplished works of this type but had enormous influence on other autobiographers. Jón demonstrates the strength of Matthías’s connections with the most prominent ideological movements of the 19th century such as Romanticism, as well as the emerging Freudian ideas on psychoanalysis. Matthías appears to have been determined to put these ideas to test in his autobiography, and in this he succeeded in memorable fashion. Lastly, the manuscript history of this remarkable document comes as a genuine surprise, and in fact leaves it open to dispute who deserves the credit for being its author, Matthías or his son Dr. Steingrímur Matthíasson. The whole story also raises questions about the interplay between people’s inner lives and the external factors that almost inevitably come to bear on the central characters in the creation of autobiographies: when is it possible to trust the truth value of autobiographies? or are they perhaps impermissible as historical sources? These questions are beyond the scope of Jón Aðalsteinn’s article but his discussion gives the reader an intimation of how problematic autobiographies can be as historical sources, as well as how alluring.

The articles mentioned so far all center on methodological issues: they discuss in one way or another questions surrounding the most appropriate methods and sources to use when researching particular topics. The essays that follow are rather examples of how the methods of microhistory can be applied and implemented. What they have in common is that they take a discrete body of material and subject it to these methods in the analysis of phenomena and events of some former time. The articles are based on basic demographic research into subjects such as widowhood and the fostering of children and provide opportunities to compare the alternative treatments offered by microhistory and historical demography, and the considerable differences between them.

Kristrún Halla Helgadóttir contributes a fine article on Sigríður Pálsdóttir, a 19th-century woman whose entire life seems to have been dogged by trials and misfortunes. In an essay called “Hagir prestekkna” (The circumstances of ministers’ widowes) Kristrún Halla uses the long and involved story of this woman’s life to shed light on the conditions of widows in the 19th century. The research is based on around 250 letters that Sigríður wrote to her brother Páll Pálsson, secretary in the office of the deputy governor, the first written when she was only nine, the last just a month before her death and in her 60s. The essay is a testament to the value of the microhistorical approach since it deepens our understanding of the conditions of women in Sigríður’s position in a much completer and more rounded way than previous research has done. Kristrún Halla makes use of the strengths of demography to build a solid framework for her article. Her methods and treatment demonstrate the usefulness of microhistory in investigating women’s history, viz. in allowing the story to come out from the standpoint of the women themselves. Generally disparaged and neglected, letters like those used in this article can be crucial to our ability to probe into the world of women. The low value placed on such sources has tended to result in women’s history being passed over in silence. In this regard it is worth citing the comment of Páll Eggert Ólason, who cataloged the correspondence of Páll Pálsson, Sigríður’s brother, and who, noting that Sigríður’s letters had been preserved among Páll’s collection, remarked that they could hardly be counted worthwhile reading material!

Monika Magnúsdóttir’s approach has similarities to Kristrún Halla’s in the sense that she takes as her starting point the findings of a scholar who has grappled with the interpretation of statistical sources. In her case, this is an article by Gísli Ágúst Gunnlaugsson that appeared in the American Journal of Social History and dealt with foster-children in Iceland and their conditions. Monika names her article “Það var fæddur krakki í koti: um fósturbörn og ómaga á síðari hluta nítjándu aldar” (A child was born in a shack: on foster-children and paupers in the second half of the 19th century). As the name suggests, she sets out to account for the different conditions under which children were fostered in Iceland. She uses personal sources such as autobiographies, letters and diaries, and collectively these sources enable her to put a very different light on the conditions of foster-children from what emerges from the conventional, institutional sources or statistical demographic analysis. Monika succeeds in bringing out the world of the child as seen through their own eyes and manages to increase our understanding of people’s attitudes to children, especially poor children, in this period. In many households the duty of care placed on those charged with bringing up children was shouldered conscientiously and the children seen on their way into life. In this the homes of church ministers often provided notable examples. But as Monika touches upon, there were plenty of homes that failed entirely in their duty and exploited and abused their charges in various ways. But it should be borne in mind that the distinction between natural and proper remedies in the bringing up of children and a relationship based on a demand for a heavy work input was extremely unclear in the minds of many parents in the second half of the 19th century.

Svavar Hávarðsson’s article deals with the district officer, local chief and big farmer Björn Halldórsson of Úlfsstaðir on Loðmundarfjörður in the east of Iceland. Björn kept a diary for nigh on 30 years which preserves a record of the extraordinary range of his activities. Svavar discusses specifically how Björn reacted to death during his life, a subject in which he had unique experience through his position of being called out regularly when neighbors fell sick as a result of his reputation as a practitioner of folk medicine. He also built coffins, including many for children. Björn himself was blessed with a large family and was constantly mulling over what the future held for his children. His reactions to grief are extremely illuminating since he expresses himself openly and candidly on his own feelings. Svavar pays particular attention to the solace afforded Björn and his contemporaries by poetry of various kinds in their attempts to come to terms with grief. Here Svavar is testing theories that have been expressed elsewhere regarding the relationship between death and poetry and he adds appreciable strength to the connection scholars have claimed to identify between them. Svavar’s article demonstrates beyond all question the potential power of diaries as historical sources. Here, purely in passing, it is interesting to note that no less than seven diaries have been preserved from the Loðmundarfjörður region from the same time as Björn was writing his, i.e. the second half of the 19th century, at a time when the entire community numbered only ten farms. There can hardly be another example in this country of such a large number of diaries being preserved from a single community, and these sources offer powerful opportunities for research into the daily life of people of the period.

The articles by Svavar, Sigrún, Kristrún Halla, Davíð and Jón Aðalsteinn all arise from longer-term projects they are currently working on and one may expect further results from their work in the years to come. Sigrún, Kristrún Halla and Davíð have each received support grants for their research or projects related to them from Nýsköpunarsjóður námsmanna (the Students’ Innovation Fund) and the Fund has been a critical factor in their being able to undertake wide-ranging research into the letters and diaries preserved in the manuscript department of Landsbókasafnið (the National Library). All these three, together with Monika Magnúsdóttir, are now taking their first steps on the public arena of history, though most of them have already published articles in Sagnir, the journal of history students at the University of Iceland. It is thus particularly gratifying to see how significant these first ventures into the world of scholarship have been, since all the authors have clearly managed to open up entirely new areas for study.

The finishing touch to the book is provided by Inga Huld Hákonardóttir. Of all the members of the group Inga Huld is the one with the most experience of authorship. She has been working on personal sources of one form or another for several decades and summarizes her academic past in memorable fashion in an article entitled “Annáll sigranna” (Annals of the victories). The article drects a powerful spotlight on positivism, drawing attention to the adverse effects its ideas and methods have had on research into women and many minority groups; the limitations of this methodology have resulted in our contemporary vision of the unwinding of history becoming simplistic and one-dimensional, if not downright misleading. It may be said that it is precisely here that microhistory and the historical analysis it is built on have most to offer. Through these new approaches we are able to shift the center of gravity of the subjects we take for consideration and focus on different aspects, as for example in relations between the sexes (gender studies) and other comparable areas that have been largely neglected by historians of the positivist school. A willingness to look at historical phenomena and events in new ways by deconstructing them is one of the most important tasks facing historians of the future and in this microhistory has a key role to play, as many of the essays in the book demonstrate. Inga Huld’s exhortations that historians need to face up to the tasks of tomorrow with open minds and free themselves from the shackles of tradition – which have, for instance, resulted in whole areas of study being left unexplored – are timely and set forth with moderation and assurance.

As mentioned earlier, the book Einsagan – ólíkar leiðir (Microhistory – conflicting paths) is the product of a symposium of twenty scholar linked by a common interest in addressing new subjects in ways different from those used hitherto. All the contributors have given freely of their time and the publication of the book has been financed by the group itself. We, the editors and also organizers of the Microhistory Group, have derived great pleasure from this interaction with our colleagues. Work of this kind is invaluable to professional scholars, giving participants opportunities to raise various problems that academic research inevitably throws up and seek advice from their friends and fellows.

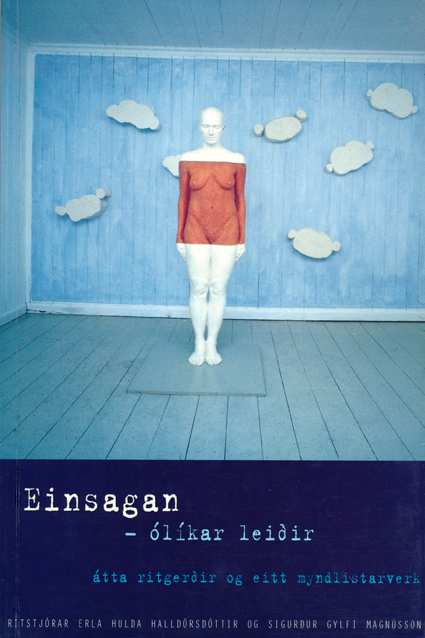

Some time last year one of the editors was out walking down in town and happened on an exhibition by the sculptor Ragnhildur Stefánsdóttir. Among the pieces on display was one that bore the name Ein-vera (Sole-itude). We were immediately struck by both the work and its name and it came to light that Ragnhildur had been thinking along very similar lines to us in our attempts to come to grips with microhistory, though she was entirely unaware of our academic endeavors. This of course raises insistent questions about how ideas cross over from one cultural realm to another and this little story should really be seen as a spur to greater collaboration between people in different areas of society. What we share with Ragnhildur is that we are all dealing with creation, she in the field of art, we in the field of history. The methods of scholars and artists are different but the conclusion is the same: in order to be able to understand the workings of history we need to think about the small units within society, for example private individuals. The methodology of microhistory calls directly for a cross-curricular approach and hopefully we will get to the point where scholars, artists and writers can join hands and work on the pressing subjects of the future with an open mind.

Ragnhildur kindly gave us permission to use a picture of her work Ein-vera on the cover of the book and she says a little about it in the introduction. The picture is by the photographer Spessi and the cover design is by Alda Lóa Leifsdóttir. We offer all these people our warmest thanks and consider ourselves privileged to have benefited from their expertise.

In publishing the book we turned to the University of Iceland Press and were received with help and support from the manager Jörundur Guðmundsson and from Birna Lísa Jensdóttir. The typesetting was done by Sverrir Sveinsson, printer. We thank them for their help and extensive technical advice.

The descendants of Maid Imba may have discarded their national costume but they have a long and arduous road in front of them, a journey that will doubtless test our academic powers to the utmost. The die has been cast. The rest is up to us.

Reykjavík, 24 December 1997

Erla Hulda Halldórsdóttir and Sigurður Gylfi Magnússon